Impact on the Surrounding Areas

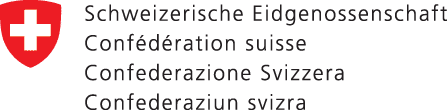

In the case of Chernobyl, large quantities of radioactivity were released very quickly after the start of the accident. This made a prompt evacuation impossible, and not only the on-site operating staff but also the population in the surrounding areas were exposed to quite high doses of radiation. Over the following days and weeks, a total of rather more than 100,000 people were initially evacuated within a radius of 30 kilometres, followed by well over 200,000 more in subsequent years. The radioactive cloud that was transported to high altitudes due to the explosion and the fire led to differing degrees of contamination in parts of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia as well as large areas of Europe. Hundreds of thousands of workers (“liquidators”) were deployed in order to deal with the accident and, more specifically, to prevent further releases by enclosing the stricken reactor in a sarcophagus, as it is known. In particular, some of the individuals who were deployed immediately after the accident therefore received very high doses of radiation.

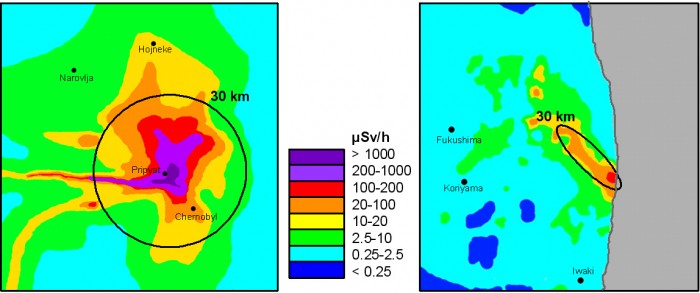

According to estimates by the Japanese authorities, the radioactivity released until today at the Fukushima site is equivalent to about one tenth of the amount released at Chernobyl. This radioactivity spread from Fukushima through the atmosphere to a lesser extent, so the contamination tends to be concentrated more heavily on the surrounding region. A substantial proportion of the radioactivity was carried out over the Pacific due to the prevailing westerly winds, and highly radioactive cooling water also reached the sea. As several days passed before major releases of radioactivity occurred, prompt evacuation of the population was possible (involving about 70,000 to 80,000 people within a radius of 20 kilometres). The evacuation was later extended to specific, more heavily contaminated areas outside of this zone. The number of intervention personnel required to deal with the accident at Fukushima is considerably lower. According to the Japanese authorities, 28 of the 300 or so workers deployed at Fukushima Dai-ichi received doses of more than 100 millisieverts; consequently, no worker has yet attained the limit of 250 millisieverts as stipulated by the authorities for emergency cases.

Although it is difficult at present to assess the medium- and long-term consequences of the Fukushima event for people and the environment, it may be assumed that in overall terms the radiological effects of the Fukushima accident will be significantly less than those of Chernobyl. A prohibited (restricted) zone of about 4000 square kilometres was set up around Chernobyl; this zone still cannot be used at present, and will remain unusable for a long time to come. It is not yet possible to state how long the prohibited zone of 20 kilometres around the Fukushima Dai-ichi site will remain in place. In addition to the radiological consequences, another factor should not be forgotten: the psychological consequences of fear of radiation, and of the uprooting of the people who had to relocate.